Final Rev saved 5/14/10 14:15

=====================================

The

HTML version was put together in September 1999 more or less from the

original. Although this story may be a bit personal, I felt it

was too important to explain, in this version meant for family, the way

things are in Cuba.

2009: a satellite image of Havana. Go to http://maps.google.com, select

Havana,Cuba and zoom in for details.

Most places referred to in the text are

here. In the upper right, across the harbor,

is La Cabaña, which we visited Tuesday. Staying at the top of

the map and crossing the harbor to the main part of the city, from East

to West are Old Havana (Habana Vieja), Central Havana (where the "La

Habana" indicator is, above), Vedado, and Miramar (both indicated on

the map).

Our hotel, the Plaza, is located between the

two vertical yellow lines by the third "a" in Habana at the Parque

Central (the left yellow line is the Prado). Across the Parque

Central is the Gran Teatro. The Malecón runs along the

Caribbean at the top of the picture. San Lázaro

is the street just south of the Malecón.

Calles Obispo and O'Reilly run East-West in

Habana Vieja, and the Plaza de Armas and the café La Mina are on

Obispo near the water. Consulado and Galiano run North-South to

the West of the Prado.

The University, where we saw the rugby

practice is just below the words "Calle 23", in the vicinity of a

stadium which can barely be seen on the map. The Hotel New York,

where Manuel Lagos lived out the end of his life, is in Chinatown, just

below the university, on Calle Zanja.

The great Necropolis of Colón is the big white rectangle to the left of center.

Our

relatives

are

scattered

throughout the city. Alicia and Roxana live in Central

Havana, as does Micky; Diana lives in Vedado. Mercedita lives in Cerro,

and Isabelita and José Antonio live in Santos Suárez.

Un

fuerte

abrazo,

Rodolfo”

(

.

.

.

[Best

wishes to the family] . . .

Please prepare

yourself mentally, because this isn’t the country you once knew, the

COMUNIST

DICTATOR has destroyed everything, I can tell you that today it’s the

poorest

and most repressive country in

OK,

Rudy,

I

thought,

let’s not get too carried

away, I

mean I know things are bad, but that’s a bit much.

Then I thought, “Why do these Cuban exiles

exaggerate everything?”

Nevertheless,

after

having

spent

a week there,

I must say that though I had thought I was prepared, I was not. By the second day there I was infused with a

profound sadness, even - briefly - a desire to leave immediately.

I was sorry I had gone.

If

I

didn’t

have

relatives

there, however, I

would never

have known.

Aside

from

the

beat-up

appearance of many of

the

buildings, most tourists, I’m sure, don’t have a clue.

Especially the ones that just go to the beach

hotels and never leave their little comfort zone.

By

the

time

we

left, however, I was able to

appreciate

the way people retain the ability to enjoy the small things in life,

and the

way they manage to survive, and face with humor, the most depressing

and even

humiliating circumstances.

Now

I

can

say

that I’m glad we went: it was

wonderful to

see old relatives and meet new ones.

Overall it was an enriching experience, and I’m sure we’ll do it

again. And I recommend it to you, if

you’re prepared to visit our relatives (and not just places), and try

to understand their lives and the ambience in which they live.

I

decided

this

family

research was not – for

me, anyway –

something that could be done without being “up close and personal.” A trip was necessary.

Antonio LAGOS (Papa) and Pepita BESTEIRO

(Maina) wedding,

Uncle Dominic

Aunt

Betty

Uncle Mario

40

years

is

a

long time.

I

was

to

see

very many

When

people

with

Cuban

connections got a whiff

of our

intentions, we were overwhelmed with clothes, medicines, and other

goodies for

friends and relatives. We had read that

the baggage allowance was 20 kg per person, and we knew we were over. Roos Travel, our agent, said that Hola Sun,

the package provider, has a deal with the airlines that allows 30 kg

(66 lbs)

per person. We hoped so.

We

drove

to

We

found

out

that,

not only were we allowed to

take 30

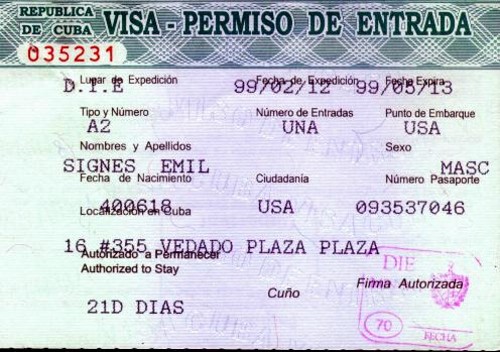

kg, but were also issued a tourist card by Hola Sun holidays. This tourist card could be used instead of

the Cuban visas we had been issued.

Therefore, it appeared, we had spent $250 for visas that we

wouldn’t

need.

We

had

lots

of

cash with us, which was

necessary because

neither Amex cards nor any credit cards on American banks are valid.

On

the

plane

to

Although

we

were

to

find no evidence that this

was true

(and cousin Diana said she had never heard of such a thing), this

conversation

convinced us that we would use our tourist cards and leave the visas

for the

scrapbook.

She

was

also

carrying

2 rolls of toilet paper

in her

carry-on.

A

portent

of

things

to come?

The

plane

arrived

in

As

we

exited

the

customs area at the airport, a

pair of

people grabbed our bags and put them on carts.

Not wanting to cause any waves, nor knowing the protocol at the

airport,

we let them take them. We found a

Havanatur representative who was able to direct us to the proper bus

for our

hotel (transfer to and from the hotel was included as part of the

package). We followed the guys with the

cart and got there and gave each of them a dollar.

At that point a third person, who had

accompanied them, said angrily. “¡Coño! ¿Y yo?”

(Hey – what about me?!) I gave

him a dollar and they all disappeared.

This

was

our

first

exposure to the “jineteros”

(hustlers), who are omnipresent in

We

joined

three

people

in the minibus who had

been there

about half an hour waiting to be transported to their hotels, and we

waited

still longer. Finally, just as we were

to arrange to take cabs, the driver appeared and we headed off into the

dark and

mostly unlit suburban

We

arrived

at

the

hotel after

I

left

Heide

to

talk to the relatives while I

checked

in. The guy who took our five bags to

room 453 was very friendly and helpful, and I decided to give him a $5

tip. When I reached into my pocket, I

found a single along with the five, and said, what the hell, so I gave

him $6.

With

everything

checked

in,

I returned to the

group, who

was sitting in the lobby quietly talking, and asked “Well?

Aren’t we going to do something? Let’s

have

a

few

drinks, maybe get something

to eat, party on down, whatever?” I was

met with a quiet smile (which I later was to interpret as “You don’t

get it, do

you?)” The words that they spoke were,

“Well, we thought you’d be very tired after this long trip.” I looked around and saw there was a bar in

the hotel, and invited everyone for a drink.

We

went

in,

put

a couple of tables together,

ordered a

round of drinks, and sat and talked for about an hour or more.

I

don’t

know

whether

I specifically brought the

topic up,

but the matter of salaries came up, and we were told, in detail, just

what

everyone made. It appeared that

professional people were earning in the neighborhood of $10-15 per

month, persons with probably the equivalent of an associate degree,

about $7 per month, retirees on pension about the same.

José Antonio and Heide at hotel bar,

Saturday night

Alicia and Roxana

I

made

a

quick

calculation – if the average

Cuban

professional made 200 pesos per month (a hair less than $10), then the

$1.50

the hotel was charging for domestic beer would represent more than 15%

of their

monthly income. To put this in American

terms, for an American making $36,000 per year, 15% of monthly income

would

represent a price per beer of $450. The

round of 8 I had just bought would cost $3,600.

That would be a world we certainly couldn’t afford to be in at

our expense. I realized then that

everything we did

together would be entirely at our expense. Not that I had a problem

with that;

it was just the enormity of the disparity that stunned me.

Dollars vs.

Pesos

Until

1993,

the

possession

of dollars in

The

shortages,

and

the

lines, were a great

difficulty for

a

With

the

legalization

of

the dollar, and the

concurrent

decision to encourage tourism, absolute shortages started to lessen. They were replaced, however, by products

that, while available, were priced in dollars at prices similar to

those we

would pay in the

How

can

anyone

do

this?

I innocently ask. It turns out

there are a few ways.

Firstly,

the

Cuban

exiles

in the United States

now number

about 15-20% of the population of Cuba itself, so there are a number of

families with relatives in the US who manage to get dollars to Cuba

(mostly

illegally, but as I’m told repeatedly this week, “Almost everything in

Cuba now

is illegal.”)

Then

there

are

those

that earn dollars. Prominent

among these are waiters, maids,

taxi drivers, and of course, bellhops.

Interestingly, I’m told that, because of the desirability of

that

profession, bellhops have to “buy themselves in” (under the table, of

course). Think of it as tuition for

Then

there

are

employees

of foreign companies,

and of

course hustlers (jineteros), whores (jineteras), etc.

People

with

regular

jobs

also moonlight. Thus a

hardware engineer with whom I spoke, who earned $15 per month, through

repairing computers, etc., has been able to own

his own

computer and also be on the Internet.

One

theory

as

to

why illegal activities are not

only

everywhere, but also everywhere tolerated is that, first of all, it is

recognized that they are necessary to survive.

Secondly, it means that virtually anyone is set up to be found

guilty of

something if the government so desires.

Whether

overtly

or

in

a quiet and unobtrusive

way, the

government seems to have an hold on just about everyone.

Engineers

and

doctors

Commenting

on

moonlighting

professionals

the

following

observation was made. Engineers, who

often have technical skills, can often find some activity to supply

them with

dollars. “But what can a doctor

do?”

I'm

told

that many

taxicabs

in

Perhaps

they

should

be

looking for bellhops to

sponsor

them.

Traveling

Given

their

financial

conditions,

it is not

easy for

Cubans to travel abroad. Nor are they

usually allowed to. For financial reasons, it’s even difficult to

travel within

José

Antonio,

however,

in

a comment that

was to be echoed

several times during the week, wasn’t too concerned about this facet of

life. “People tell us how sorry they are

that we can’t travel”, he said. “We

really don’t worry about that; we’re too concerned with figuring out

where the

next meal is coming from.”

Convertible

pesos

I

had

laughed

at

the exchange rate published in

the

currency table of a Cuban newspaper (all newspapers are published by

the

government, of course), which showed the peso at 1 to 1 with the dollar. I was able to receive 21 pesos to the dollar

at a CADECA, a government-run change agency, and according to the

Internet, the

actual exchange rate was 23 to the dollar.

I suppose, in retrospect, they were talking about convertible

pesos. I hope they were.

You’ve

heard

the

expression

“as queer as a

three dollar

bill?” Well, I got one in

My

completely

uneducated

guess

is that

But

back

to

Saturday

night.

Diana’s husband Simón Goldsztein (the

mysterious

“z”

had

been added

erroneously by Cuban officials to his father’s marriage certificate,

and is now

part of the official spelling) showed up as everyone else left. He joined us for a beer, and among other

things, told me of his stepmother Baruja, and two sisters, Fania and

Frida, who

had left for Miami in 1948 and never been heard of since.

I told him when it came to family things I

was Sherlock Holmes. So now I have a

family discovery project: find two women with the all-too-common

surname of Goldstein,

who have probably married, and may even be dead, last heard from in

Know

them?

Simón

When

Simón

and

Diana

leave, around

Breakfast

is

part

of

our package, and it’s a

huge buffet

spread, with lots of choices. Among them

are lots of fruits – oranges, pineapples, mango, papaya, etc. Ironically, so we're told, fruit is often hard

to come by for regular Cubans. But it's always available at the

tourist hotels.

Breakfast

is

on

the

top floor, on a balcony

with a nice

view of the city.

View from the

Correos, or

new

math: where 50 cents = 2

½ cents

I

changed

the

money

and went to the post office. They

were

about to sell me the stamps at 50

centavos on the dollar (i.e. 50 US cents each), but when I said, “No,

no, ¡en

pesos!, they said I had to do that “mañana.”

Afraid that mañana they would say they same thing, I

still walked out

without buying any stamps.

Later

in

the

week,

in fact, I returned to the

Post Office

and was directed to a window where I again asked for stamps – while

holding a

stack of 20 peso notes in front of the woman behind the bars. Before I could say anything, she said

“¿Pesos? Next window.”

And there I got 80 stamps for a total of 40

pesos, or $2.00. Had I got the identical

stamps at the first window, they would have cost me $40.

Being

there

on

Sunday

we missed it, but we’re

told that

during the week the place is full of little kids taking ballet lessons. That would have been neat to observe. (Note of July 14: this is where the kids are

practicing in the movie “The Buena Vista Social Club” during the

segment on

pianist Rubén González.)

One

of

the

things

Heide and I really wanted to

do while

we were in

The

zarzuela,

“María

la

O”, by Ernesto

Lecuona, was to be

one of the highlights of our week.

Preparing the set for María la O

Walking

down

Calle

Obispo

we saw lots of major

renovations, another indication of the Cuban government’s commitment to

the

tourist industry (how things change!)

Simón pointed out a few places to eat that seemed to be

inexpensive –

pizza was one, but we gave it a pass.

Finally we came to a place that Simón recognized. “The food is cheap here, you can get a glass

of beer for 3 pesos (15 cents), etc.

Only

problem

was,

there

was a “cola” – a queue,

a

line. A long one, in fact.

I had read about these lines in “Trading with

the Enemy”, and was finally to experience one.

The ethics of the line were, you found “el último” (last

person in

line), and made sure that person knew you were behind him or her. At

that

point, you could go about your own business, returning occasionally to

check

the status of the line. Of course, if

the person in front of you got served before you returned, you lost

your place

in line and had to start from scratch.

The estimate for this wait was about an hour and a half. We continued our walk.

We

went

further

down

Calle Obispo, then walked

along the

harbor to the Presidential palace and headed back.

Among the sights we saw were the Castillo de

la Real Fuerza, the Iglesia del Santo Ángelo Costudio, a really

neat old church

where José Martí was christened, Batista’s old

Presidential Palace (now a museum

of the Revolution), the Granma memorial, and many other sites of Old

Havana.

With Diana at the Castillo de la Real Fuerza (

Diana

continued

taking

Heide

and me along old

streets

while Simón checked the line . . . eventually he found us and

motioned us back.

When we got there, it still wasn’t time, so the three of us waited in

the lobby

of the “Ambos Mundos” hotel. Diana had a

botched hip operation a few years ago (maybe the guy came straight to

the O.R.

from driving his taxi) and is forced to walk with a cane, so it seemed

appropriate that after two hours of walking she rest a bit. Simón waited by the restaurant, three

doors

away.

The

security

person

at

the Ambos Mundos paced

around

while we sat and waited. He probably

recognized that Diana was a Cuban, and the tourist hotels aren’t too

crazy

about having Cubans inside, some of them outright forbid them. In fact, he left us alone, and Simón

finally

came to get us.

After

another

10

minutes

on the line (we were

now past

the 2 hour mark), a friend of Simón and Diana’s showed up, and

after being

introduced to us said, “You know, they only allow Cubans in there.” Simón went to check, and it was true. Diana went ballistic and went in to have a

word with the management. The answer: “I’m sorry, but I’ll lose my job

if I let

them in.”

A

compromise

was

struck,

and we were sold 4

meals in

cardboard cartons. They each consisted

of half a chicken and an ample portion of black beans and rice. The total price was 100 pesos ($5 total, or

$1.25 each). We went to the nearby Plaza

de Armas, and sat down on the bench to begin our meal, as stray dogs

hovered

nearby waiting for scraps. One problem –

we had no cutlery, which wasn’t too much of a problem with the chicken,

but . .

. rice?

With

typical

Cuban

ingenuity,

Diana ripped off

a piece of

cardboard from the top of the box, cupped it into a U-shape, and –

voila! – a

spoon emerged. We had a great meal, and

the dogs devoured the scraps. A park

cleaner seemed to know the dogs and looked out for the strays: she came

over

and screamed at one of dogs “You have a home, leave the food for ‘La

gaviota’,

who has to feed on scraps!”

We

headed

back

to

the hotel on

When

we

got

to

the hotel, we were met by Miguel

Ángel,

son of Tío Domingo (AKA Uncle Dominic), and

Miguel Ángel’s children Miguel Ángel (Miguelito,

or Miki) and Mercedes

(Merceditas or Mercy), and Merceditas’ husband Enrique. They

joined

us

for

a beer and brought new

family information for the tree. Mercy

invited us to join her family for an evening trip to the Cabaña,

a huge fort

across the harbor.

Merceditas & Enrique

Interestingly,

one

of

the

scathing criticisms

of the

Batista regime was the phenomenon of “tourist apartheid.”

Well, folks, tourist apartheid is alive and

well in Castro’s

At

any

rate,

we

brought the suitcase downstairs

(where we

were given a dirty look by security – I don’t know if he thought we

were going

to sell it, or what – but I didn’t care).

The idea was to get it to Diana’s

father Bebo’s house. This meant

taking

a taxi, which sent Simón scurrying to negotiate.

If

you’re

a

foreigner,

you normally just take a

local

cab: most of them are metered and the rates are reasonable (although

there are

some that are a lot cheaper than others, and in the non-metered cabs

you’d

better negotiate beforehand).

Habaneros,

however,

take

“taxis

particulares” (private

cabs) where they can negotiate

rates. Usually these are just ordinary

people with no taxi license that need to pick up a buck or two. At any rate, Simón negotiated a $3 cab

ride

to Bebo’s house in Vedado. All the way

there, the driver kept saying “Are you sure you’re all Cuban? If they catch me with paying riders, they’ll

fine me. I have a wife and child and I

can’t afford that.” Diana teased him: “Yes, we’re all Cubans. From

When

we

got

to

Bebo’s, Diana had to shout up

three

stories to get the door opened, as the bell doesn’t work.

We walked up to the apartment where I had

spent a month in 1955. It didn’t seem

that much different, although the furniture seemed older, and the rooms

sparsely

furnished.

Bebo,

who

is

nearly

80, seemed in fine spirits

and sharp

as a tack. We also met Diana’s son

Arturito and his wife Maribel, who is pregnant for the first time after

nearly

13 years of marriage. Finally, we met

Diana’s 17-year old grandson Eduardo, her daughter’s son, and his

“novia”

Gislen, both of whom also live with Bebo.

[Note

of

7/30:

Maribel

gave birth, by Caesarian

section,

to an 8 ¼ lb. baby boy, Mario Arturo, at

The residents of the 3rd floor of this house in Vedado.

Top: Bebo,

Arturito, Maribel.

Bottom: Eduardo, Gislen

Since

the

revolution,

although

people

theoretically own

their houses, they’re not allowed to sell them.

In fact, they can’t even move unless the people into whose house

they

are moving move simultaneously. Diana

told of one case where 21 simultaneous moves were necessary (like a

huge and

complicated trade among sporting franchises). When things like this are

arranged, the entire set of moves has to take place in a single day. There is at least one place, on the Prado, a

wide boulevard in Old Havana, where people gather informally to arrange

these

mass moves.

As

a

result

of

the

housing situation, it is

quite common

to find several generations of a single family living under one roof. Thus Bebo, his grandson and granddaughter in

law, and his great grandson all live in his house; Diana’s daughter and

the

rest of her family in another.

I

don’t

think

the

original plan called for us

to eat

there, but it was after

Taking

into

account

that

Diana and Simón

live on the

seventh floor of a building whose elevator was not working, he put

himself out

quite a bit just for us. Imagine, too,

what

it must be like climbing seven stories on a regular basis with a bad

hip and a

cane. The elevator fails often – at one

point they went 13 consecutive months without a functioning elevator.

They

were

still

“working”

on the elevator when

we left

Our

meal

–

for

nine people -- consisted of

these two

items, a small dish of tomato slices and a dish of onion slices. We ate sparsely, and our hosts seemed to do

the same, trying to make sure we had enough to eat.

I was happy with tomato and onion sandwiches

(with Motzah instead of bread), but I suspect that kind of meal gets

old after

a while.

During

our

meal

we

learned a little more about

the salary

structure and its implications. Upon

graduation from college, engineers all start out at

exactly

198 pesos (at the 21:1 exchange, that’s $9.43) a month.

Then after a few months, it goes up to 220,

then 240, etc, (I confess I don’t remember the exact figures, but in

absolute

terms it goes from almost nothing to almost nothing in neat

pre-programmed

steps, regardless of performance). The

result is that there is very little incentive for people to work hard

to pursue

a career. For two reasons: one, it doesn’t

matter how you perform, you’re going to get the same salary. And two, this salary is absolutely a trifle

compared with the cost of living. In a

land where waiters and bellhops rule, why bother to be an engineer or a

doctor?

Eduardo

notes

that

he

plans to go to college –

but

because he enjoys studying, not because he has any illusions about its

helping

him cope with life afterwards.

The

lack

of

incentives

also leads to lack of

productivity: I’m told by many people that Cubans “go to work”, but

they rarely

work. During the week we’re told the

following anecdote: A Japanese company moves to

At

the

end

of

the day, the Japanese workers

tell the

Cubans, “It was really enjoyable spending the day with you. We’re sorry we couldn’t show solidarity with

you in your strike, but then we’re not Cuban . . . “

Rationing

is

a

way

of life in

I

also

notice

during

the week that no one

refers to

Castro by name. One common substitute seems to be to say “he” while

stroking an

imaginary beard.

Among

our

family

are

people that favor Castro

and his

policies (which are still referred to as “the revolution”) and those

that

don’t. Likewise among other people with

whom we spoke there seemed to be varying degree of enthusiam or lack

thereof regarding the government. During the entire week, no one

came out and attacked him, although the failures of his policies were

noted

repeatedly.

Political

correctness

also

plays

a part in

Cuban

life. People are expected to attend

meetings of the local Committee for the Defense of the Revolution, and

other

government based activities. If they

don’t, there are no dire consequences, but people “remember” who did

and who

didn’t fulfill their obligations whenever there is a “plum” to hand out.

Here is the format of one such summons:

(SUMMONS.

“Compañero (Comrade) -- address: You are summoned for the

Financial

Report of the DELEGATE of our district no. . . We expect you promptly”) (CDR = Comite para

la defensa de la Revolución)

(Note:

the

above

is

not a summary of this

evening’s

discussion, but a compilation of things heard throughout the week. Nevertheless the evening’s discussions were a

good entry into the system and its consequences.)

The

Tropicana

is

one

of the few clubs to have

survived

the entire Revolutionary period and is a tourist highlight. I was determined that, after 44 years, we

would finally attend the Tropicana, and I invited both Diana and

Simón to join

Heide and me.

Diana,

however,

said

she

had heard that the

Tropicana

cost $75 per person, and that while she appreciated the offer, if that

were

true, she couldn’t even imagine spending that kind of money, and

wouldn’t go.

When

I

checked

the

price, I found out it was

possible to

do the Tropicana for closer to $50, on the cheap.

Still, given what I now knew, I had to agree with Diana. Scratch the Tropicana. Given

what

I

now

knew, it would have been

obscene to spend that kind of money on a cabaret.

The

next

day

we

gave Diana the money we would

have spent

to take the four of us to the Tropicana.

And we never missed it.

Tropicana [1955]

Oh

yes,

I

forgot:

before we left Bebo’s, I made

a quick

trip to the bathroom.

There

was

no

toilet

paper.

And the toilet didn’t flush.

We

had

only

been

in

After

44

years

of

isolation, I have returned to

We

repeat

our

walk

down Calle Obispo, looking

for some

presents to bring home. Still not in a

mood to spend money, we get nothing and our lunch consists of a ham and

cheese

sandwich at the hotel.

I

had

brought

José

Antonio a “care”

package, including

clothes, medicine and some US dollars, from a good friend of his in

We

made

a

First,

however,

we

were

to meet Diana at

Alicia’s house

in Centro Habana, then walk to Carlos III,

Alicia

lives

in

the

house in which she was

born, the only

one she has ever known. She lives with

her husband Juan, her daughter Roxana, and Roxana’s 7-year old son

Jonathan. Juan has been suffering from

Parkinson’s for more than 12 years, and although he remains at home, is

virtually uncommunicative.

Jonathan

Although

Alicia,

who

is

small and frail, has

had to

transport Juan, a large heavy man, between his bed and his chair –

wherever he

has had to be, in fact, until recently she had not been able to get a

wheelchair for him. After she dropped

him four times, however, she finally was able, after much red tape, to

get the

wheelchair. This has made her life

easier, she says.

Since

Roxana’s

divorce,

she

and Jonathan have

lived with

Alicia, and Jonathan (who is in the first grade) is home today as his

teacher

had to go home sick from school. Alicia

urges him to show us some of his homework, and what I see amazes me. Among the math problems, for example, are 16

- x = 14. Now I don’t know when I first

learned to use “x”, or when my kids did, but it sure as hell wasn’t in

the

first grade.

Likewise,

the

Spanish

homework

he has seems

pretty

advanced to me.

Jonathan

has

just

reached

the age of 7, which

is a

critical year in a child’s life. The

government provides milk (powdered milk, I saw no other kind during my

entire

trip) for children until they reach the age of seven, then it is cut

off, and

families have to rely on the ration book.

The rationed amount of milk costs 2 pesos (10 US cents), but

there

hasn’t been any available for a couple of months. To

buy

milk

outside

the government rations

would cost 20 pesos (a dollar) for the same quantity.

Alicia

had

detached

her

retina in an accident

and then

re-detached it while it was healing, while rescuing Jonathan from a

fall, and

is now blind in one eye.

On

top

of

everything

else, Alicia, like just

about

everyone, has to moonlight; she tutors two groups of children, twice a

week.

It

is

obvious

Alicia

has led a difficult and

confining

life over the last several years.

Diana

was

to

arrive

at about the same time we

were, and

we came late. It is 1½ hours after

our

scheduled arrival time. Alicia notes

that she probably hasn’t been able to catch the “guagua” (bus). There is no bus schedule and there are not

nearly enough guaguas to meet the demand.

Sometimes, we are told, people can wait 2 hours or more without

a guagua

passing by. This can be not only very

frustrating, but even worse if it means you arrive late at work because

of

it. Roxana’s route to work includes

looking for someone she knows driving a car, while walking, and

possibly

catching a guagua if one comes by.

Private

cars?

Forget it. Although there are some

(and everything you’ve heard about 40s and 50s American cars all over

the place

is true), most cars are company-owned and right now it seems quite

impossible

for Cubans to get their own cars.

Bicycles, however, have become a quite popular substitute.

This

is

quite

a

change: Maurice Halperin notes

that in

1959 there were more private cars in

When

I

had

called

to give Diana our arrival

time, she

said they would meet us at the hotel, because it was “a bit difficult”

for them

to get to the airport. This, it seems,

was quite an understatement. Getting to

the hotel must have been difficult enough.

A

diabolical,

and

uniquely

Cuban, solution was

devised to

relieve the transportation shortage: the “camello”, or camel. Towed by a tractor, it is a long container

with roughly a camel-like shape (two humps) that can accommodate 300

people. We saw lots of camellos during our

travels,

always packed to the rafters with people.

The price is right – one cent – but the conditions horrible with

everyone packed together, and petty theft is rampant.

Alicia notes that she and Roxana came to the

hotel to meet us in a camello, and that the man standing next to Roxana

was in

heavy-duty molesting mode, which, because of the tightness of the

situation,

Roxana could do little about. Until,

luckily, a man holding a baby came by and called the molester off.

Camello in

We

walk

to

the

Carlos III,

While

not

crowded,

the

mall has a reasonable

amount of

traffic, so there are certainly a number of people capable of paying in

dollars. Simón says it grosses

about

$80,000 a day.

On

the

way

to

getting a cab, Simón

excitedly notices an

ice cream stand, and buys us some ice cream cones – at 3 pesos, or 15

cents,

apiece. They were awesome.

It’s

nearly

7

when

we arrive, and meet

Isabelita and her

91-year old mother, who also suffers from Parkinsons.

Her medication prevents her from shaking, but

she just sits quietly saying nothing.

We

have

a

pleasant

conversation with Isabelita,

José

Antonio and Minerva, all of whom live in the same house.

José Antonio treats us all to a pre-dinner

añejo.

I’m

asked

what

I

remember about my 1955 visit,

and

restrain myself from saying that I always remember it as a chance to

visit our

rich relatives in

I’m

still

not

sure

what the dinner plans are,

but Diana

and Simón get up to join us. Minerva

says

she

is

tired and unable to come along, but I wonder if it is

because two

unexpected people are coming. I’m not

sure just what is happening, and wonder if I am just being overly

sensitive to

a nonexistent “situation”. Then I think

again about Diana and Simón and a thought comes to mind.

Maybe

they

are

just

hungry.

Along

with

the

huge

food shortages of the early

90s,

underground restaurants began springing up in private homes. In 1994 the government legalized home

restaurants, or paladares, allowing them to serve up to 12 people at

one time. One reason for legalizing them,

of course,

was so they could tax them.

I

wonder

to

myself,

in complete ignorance, if

the reason

for the M.N. designation is somehow connected with an eventual change

to the

convertible peso.

The

paladar

to

which

José Antonio takes

us charges in

M.N. We select lomo criollo (pork loin),

and we also have salad, black beans and rice, and a couple of beers

each. I offer to pay but, as I figured, am

turned

down. I watch José Antonio count

out the

money – 8 bills of 50 pesos each: the entire meal including drinks has

cost $20

for five of us. It was one of the two

best meals we had all week. By our

standards, it was a huge bargain.

Still,

it’s

more

than

a month’s salary for him,

and I

know that he’s dipped heavily into the money his friend Juan Carlos has

sent.

We

return

to

José

Antonio’s house for

coffee. There, the majority of the people

watch a

serialized soap opera from

José

Antonio

and

I

go to work on his

computer. I install America Online, my

printer/scanner

and software and my digital camera capture software.

Then he connects to the Internet. The

connection

is

very

slow, but I still try

to get online with both my AOL and Yahoo IDs.

Finally I can get onto both. Due

to the slow connection, I pick out 2 or 3 messages and check them out.

José

Antonio

notes

with

surprise that

the screen name of

one of the senders is “tortillera”. He

wonders, “Did she know what she was doing when she selected that name

for

herself?” I say, “More than likely.”

I

have

been

looking

forward to finding some of

the houses

in which our family used to live. I

realize, in panic, however, that I forgot to bring them.

I’m pretty sure, however, that they’re in my

database, and I have a copy with me. I

reckon I can install it on José Antonio’s computer tomorrow, and

check.

We

walk

all

the

way down San Nicolás to

the waterfront,

the Malecón, but the numbers don’t seem to go as far as #1, and

the last

buildings seem to open up on the Malecón, and not on San

Nicolás. Heide notes that I may

have confused this

address with Aunt Dee’s Towaco address,

View of the Malecón from the corner of

San Nicolás

At

any

rate,

we

are now on THE famous

Malecón. In Christopher Baker’s

guidebook he says,

“How many times have I walked the Malecón?

Twenty? Thirty?

Once is never enough, for

It’s

unbelievable

how

so

many obviously nice

buildings

are rapidly decaying along the Malecón.

There is now a tremendous influx of Spanish money to restore

buildings

along this great boulevard, and you can see construction in progress at

various

spots along its length. In fact, there

are huge amounts of Spanish money being invested all over

While

sitting

on

the

Malecón wall, we

are greeted by

Pedro and Teresa, a couple who tell us all about their great paladar:

shrimp

and lots of other shellfish and seafood, all for $10.

This is interesting, because the guidebooks

say that the paladares are forbidden to serve shellfish. The

phrase

“almost

everything

in

We

walk

along

the

Malecón to an open-air

amphitheater,

climb to the top and enjoy the sights for about half an hour or so.

I

remember

a

“1”

and an “8” and the street “San

Lázaro”,

so we decide to look for 18 San Lázaro.

After a long walk, we get there.

It is in a decaying (read “typical”) area of town, and I

photograph it.

Along

our

walk

today,

as everyday, we notice

the

omnipresence of police.

Socialism.

According to what I’ve read, signs honoring socialism,

particularly the

slogan “Socialismo o Muerte” (Socialism or Death) are everywhere. While we see tons of signs celebrating the

40th year of the Revolution (which is considered an ongoing process),

we see

few direct praises of socialism. I’m

told that the new spin is to praise the gains

One of the few praises to socialism that we saw

Had

it

not

been

for a tournament in

Thanks,

however,

to

Mauricio

Sanmartín,

a Colombian now

living in the

At

the

same

time

I was getting this

information, a

Dominican Republic contact e-mailed me and asked me if I wanted to

bring a team

to Cuba and participate in a 3-way sevens tournament with them. He also told me there was only one team in

Mauricio’s

web

page

gives

an e-mail address for

Cuban

rugby, and when I contacted it, I got a brief response like “Yes, we

play

rugby. Call our captain Ramón at

555-000

for information.” While still in the

José

Antonio

arranged

to

meet us at the

hotel (I don’t

think it had yet sunk in just how difficult that must be for him), and

we

grabbed a cab to Vedado and the

The

field

is

huge,

and simultaneously we saw

multiple

baseball and soccer practices taking place.

I guess, they can fit a few rugby players on here, I mused.

In

fact,

it

was

well after

I

met

team

president

Chukin Chao, captain

Ramón Rodríguez,

and team doctor Osvaldo García González.

They gave me the run down on the history and status of rugby in

Chukin, Emilito, Ramón, Osvaldo

Ricardo

Martínez,

a

Catalan

rugby coach

from

After

five

years

of

existence, the club went

from a

miniscule number of members to about 100 or more. At

that

point,

a

second club, the Giraldillos

were formed, and they are based in the east of

Chao

noted

that

the

club members went on a

“missionary”

expedition to

To

date,

rugby

is

recognized only as a

recreational

activity and not as an official sport.

One hopes that this will change, and I imagine that becoming an

Olympic

medal sport will go a long way to making this happen.

We are all keeping our fingers crossed that

we will see rugby in the 2004 Olympics. [note of 2009: now we're hoping for

2016]

News

of

rugby

north

of the border has not

filtered down

to

I

tell

Chukin

I

may want an invitation to

visit; a rugby

tour would be a nice cultural exchange.

He says they would certainly be willing to entertain a sevens

tournament. The first ever Havana Sevens?

Hmmm. [note of 2009: we

participated in tourneys that we instigated in 2000 and 2001, and in

2009 a Canadian team participated in a Cuban Sevens; we are

looking forward to returning with a US team to a sevens tournament in

2010.]

We

return

to

the

hotel via José

Antonio’s house, and

prepare for our tour to the Cabaña.

Mercy

comes

to

pick

us up.

Her son Geovanni is the only one of our

relatives I meet with access to a car. I

am given the front passenger’s seat. I

feel a little guilty about this courtesy, because it means that poor

Miguel

Ángel is stuffed in the back with Heide, Mercy, Geovanni’s wife

Yohanka and

their son Daniel. But the guilt passes

quickly; it’s comfortable in front.

We

drive

through

the

tunnel under the harbor

and park at

the entrance to la Cabaña. La Cabaña, built in 1764-74

following the British

invasion, is the largest fort in the

Miguel Ángel, Heide and Mercedita at the

Cabaña

drawbridge

Miguel Ángel, Geovanni with his son

Daniel and wife

Yohanka at la Cabaña gift shop

I

note

on

the

plaque dedicating the statue that

it was

dedicated on

We

arrive

back

at

the hotel sometime between 10

and 11,

and figure it’s too early to go to bed.

We

finish

the

evening

at the hotel bar. We

realize that once again we have forgotten

to eat since lunch and have a ham and cheese sandwich.

Following

a

relatively

unproductive

morning, we

meet

Diana at Bebo’s house at

Need

an

explanation?

OK, here's the custom in

At

any

rate,

with

the records showing the date

of

exhumation and the location of the ossuary, we hope that the cemetery's

office

will be able to help us find the date of Tío Manuel's death.

This

is

not

just

any cemetery, it needs to be

described. Below is The Cuba Handbook’s

description.

"Described

as

'an

exercise

in pious excesses,'

It

was

probably

the

most well kept part of the

city we'd

visited to date.

We

go

to

the

office, where we tell Jaime, the

local

bureaucrat, that we think Manuel died in either 1960 or 1961. From his (temporary) burial place, which

Diana has in her records, Jaime notes that he was buried in an area

belonging

to a religious society, Milicia Josefina.

He can find, however, no information of his death in either 1960

or

1961. He calls on an small, old, wizened

man in military fatigues – including the obligatory Fidel cap -- to

help. "He will find the information you

need." We walk with him down Calle

1 (that's number one), slightly to the left of the entrance, past the

central

chapel to Calle I (that's the letter after H).

We take a left on I, follow it about 100 yards or so till we see

the

Sociedad Valle de Oro mausoleum on the left.

We make a right, and about 4-5 rows of ossuaries in, behind a

relatively

high cross, there's a flower box on top of a slab, about 30 inches

square, on

top of the ossuary. It says Victorina

Graciani. It holds the bones of only 3

people -- Victorina, Manuel, and Isabel Besteiro Gracciani (Aunt Betty).

Victorina Graciani marker

He

removes

the

flower

box, then carefully takes

off the

slab and goes to look in to the ossuary to find the box that says

Manuel

Lagos. I will never forget the next few

seconds as long as I live. He looks in

to the ossuary, then, his eyes open wide, he jumps back, and -- a few

moments

later -- with a look of shock, cries out, "¡Lo han profanado!" (They have desecrated it!)

The

boxes

of

bones

have been opened, the tops

removed,

and what is left of the bones, boxes and tops are intermingled in the

bottom of

the ossuary. It turns out that a few

years ago, there were a group of practicioners of "santería" (an

Afro-Cuban religion that fuses Catholicism with the religion of the

African

Yoruba tribes) who were robbing the cemetery of bones to use in

ceremonies of

"brujería" (witchcraft).

Apparently it was a band of four women, “santeras,” who were

eventually

caught. (That's not to say, however, that this particular desecration

didn't

occur at another time.) During the last

few years, the cemetery has been shut down at

The once Manuel Lagos??

Santera at Plaza de la Catedral

Marble slab with Manuel Lagos burial information

We

then

walked

back

to the office where the guy

reported

to Jaime, who scribbled 27.7.1960 supposedly in a way that was meant to

be

official on what looked like an envelope scrap.

He gave it to me with the comment "we've gone through a lot of

work

for this." I gave him a

dollar. He looked at it with

disdain.

In

retrospect,

I

wish

I hadn't have given him

squat.

[Note of 2005: it took me a long time to

realize

that even though people may only make $10 a month or less, a $1 tip

wasn't anything like giving you or me 1/10 of our monthly salary as a

tip. People can get their basic necessities for almost nothing,

but beyond that they have to pay in dollars at our rates, or 20 times

the peso rate. In other words, to tip the equivalent of of what I

"thought" I was tipping, I should have given each of those persons

$20. Think about it.]

On

our

way

out

of the cemetery, Diana meets a

friend

bicycling by. He stops, and excitedly

shows her a couple of CDs he’s just managed to get.

Apparently he’s in business getting new CDs,

and then burning pirated copies to sell for the going price of $4-5 (no

Cuban

can afford the store prices of $15-17 per CD).

Diana

notes,

“He’s

a

Mechanical Engineer. But by

now you know how much that means.”

We

stop

and

grab

a ham and cheese sandwich.

We

briefly

return

to

Bebo’s, and Diana tells us

she’s

planning dinner for us tomorrow night: she’s already arranged with the

fisherman to buy some of his catch tomorrow.

I tell her to talk to Mercedita to make sure there’s no

conflict, then

Heide and Diana go to the Carlos III to shop, and I head to José

Antonio’s to

compute.

I

install

Family

Origins

on José

Antonio’s computer and

then my family database. I haven’t put

any

José

Antonio

does

have

a note I sent him

a couple of

months ago with information about his great grandmother Joaquina who

accompanied Aunt Dee to the

We

copy

over

all

the photos I’ve taken with my

digital

camera, scan a few family photos and get online again.

AOL headline news is about a group of high

school students in

I’ve

got

a

note

from Richard, who responds that

he has

given me all the documents he had. I

remember. They’re in

By

this

time,

Heide

and Diana have arrived, and

Heide is

excited about some black coral she’s found.

Black Coral Jewelry (the earrings are imitation)

Diana

tells

us

that

her grandmother had pointed

out to

her the house that Maina [Victorina] lived in when she died, and

although it’s

on San Lázaro, it’s obviously not in the area where we were

looking. Nor could it be number 198.

We

are

dropped

off

at one of the most famous

streets (Zanja, I believe) of the Barrio

Chino, or

José Antonio, Minerva, Heide at Chinese

Restaurant

We

are

very

near

the Hotel New York, which is

at the

entrance to

From

what

I’m

told,

it is a “Cubans only”

hotel.

Hotel New York lobby,

We

got

there

at

It’s

amazing

how

things

work out. Just because

Heide

decided she didn’t want an Hatuey, we stumbled into an incredible

evening. Walking down Calle Obispo past

the “Cubans

only” restaurant of Sunday, and up to the Plaza de Armas where we had

eaten

rice and beans with cardboard, we heard a trio playing sweet music. We stopped in the place, an outdoor

café

named La Mina, and listened.

From

the

time

we

arrived (about 12:05 AM) until

2 AM, a

trio played traditional Cuban music – boleros, guarachas, lots of other

Cuban

rhythms, you name it, and a few Mexican rancheras.

They didn’t take one single break. And

they

were

fabulous.

The

trio

consisted

of

a vocalist with maracas,

a guitar

player, and a person playing a “tres”, an instrument I never knew

existed, but

forms a part of traditional Cuban music. It seems to be a regular

guitar body

with three sets of doubled strings. It

sounds sort of like a mandolin.

Trio at La Mina (Tres, Vocal/Maracas, Guitar).

Minerva is in foreground.

There

was

a

pair

of Mexicans in La Mina who

requested a

series of Mexican rancheras, and the singer seemed to know all of them. They were in their glory, and I thought,

ironically, given the backdrop of everything I’d learned so far on this

trip,

“That pair will probably go back to

Well

after

Today’s

We

walk

to

the

Hotel New York, to photograph it

in the

day time, and then walk down Avenida de Italia to San Lázaro.

Gateway to Barrio

Miffed,

we

head

down

San Lázaro to try

to find the house

where, per Diana’s directions, great-grandmother Maina Victorina died

in 1931.

It

was

a

long

walk, and in the end there is a

gas station

where we think the house should be, although the configuration of the

streets

isn’t as obvious as she described it.

(We were to find out we had missed it by about 2 houses.)

It

is

a

long

walk back along the

Malecón, and finally we

see a bici-taxi, a man riding a bike with two seats behind. We negotiate a $3 fare, but he’s sweating so

much by the time we arrive at the hotel that I give him the $4 he had

originally requested. (It would only

have been $2 by cab, but bici-taxis are a lot easier to find in this

area.)

We

lunched

on

a

ham and cheese sandwich at the

hotel.

We

head

out

to

Miguel Ángel’s and arrive

about

Then

out

comes

a

birth announcement for

Francisco Lagos

Graciani! (About the same time, Mercy

brings out an Uncle-Dominic-type drink.

Well, it wasn’t anisette, but something similarly strong.)

Francisco

Lagos

Graciani

is

Paquito, the son of

the

brother – mother-in-law marriage (Manuel Lagos and Victorina Gracciani)

referred to earlier. Traditional wisdom

has been that he was born in 1909, but I always suspected it was 1908

(details

on request), and there it was:

Paquito LAGOS GRACIANI announcement

Carmita LAGOS BESTEIRO (my mother) announcement

We

also

find

a

baptismal date for “Lolita Lagos

Besteiro”

(Aunt Dee):

There

was

no

toilet

paper.

And no running water.

The

main

course

was

aguja, a fish which the

dictionary

translates as garfish, a word I don’t even know in English. It is similar, however, to a swordfish, and

is the fish caught by Hemingway’s fisherman in “The Old Man and the

Sea.”

We

have

a

nice

salad beforehand, black bean

soup, black

beans and rice with the meal, as well as a Tropicola and some nice

Spanish

wine. Finally, fruit afterwards. It was wonderful!

My

only

concern

was

not to drink too much fluid. At

this

point, I was trying to avoid going to

the bathroom in private houses.

At

any

rate,

as

we commented afterwards, it was

a far

more rewarding experience than going to the Tropicana ever could have

been.

I

got

a

present

from Simón – a guayabera

– a uniquely

Cuban shirt (and a great Cuban invention, as opposed to the camello, a

not so

great one . . .)

Rice:

There

was

the

plan to make

Yes,” says God, “but not in your

lifetime.”

Cuban Exiles

and

Ever

since

shortly

after

the revolution, people

that have

left

Furthermore,

Cubans

that

applied

for exit visas

were

poorly treated. Once they applied, they

lost their jobs and were sent to work in the fields cutting sugarcane

until

their turn came to leave. Their names were

made public, and often their neighbors, fellow workers or schoolmates

would

taunt them. They were called traitors,

and often physically beaten up, sometimes nearly to death.

I’m

touched

by

the

amount of sympathy and

understanding I

find for the experience of the exiles.

Of

course,

the

exiles

are also responsible for

hundreds

of millions of dollars that end up in the hands of people still living

in

Another

anecdote

we

are

told:

A

woman

leaving

I

share

with

the

people at the table the

sadness that

I’ve experienced at their fate. They say

they don’t share that sadness, they’ve learned to cope.

Simón says “If I’ve got a radio and another

person has a TV, I don’t complain about the person with the TV; I learn

how to

get the most out of the radio.”

I

followed

my

plan

and slept in today. As we

were to be picked up at

Prices

here,

for

whatever

goods they had in

common, were

significantly lower than at Carlos III.

Meanwhile

I

was

finishing

addressing my

postcards. I

discovered recently that my penchant for sending postcards must have

been based

on my grandfather’s advice to my mother, in a letter he wrote to her in

Heide

and

Diana

stop

briefly at the hotel, and

I get a

better description of the house on San Lázaro where Maina

Victorina died; they

have just been there. When Heide and

Diana leave for round 2 of shopping, I go round 2 of house visiting and

photographing. Although Paquito’s birth

announcement had said “the house at 104-106 Consulado”, 104 and 106

were two

distinct houses. Galiano has been

changed to “Avenida de Italia,” but there is a double house numbered

123 and

125. The house Diana pointed out is two

doors east of Oquendo, on the south side of San Lázaro. It is numbered 819. (No,

“198”

couldn’t

have

been a misprint;

when I return home I find too many documents that refer to San

Lázaro 198.)

I

must

find

out

if there have been house

numbering

changes in the last 90 years.

My mother's (possible) birthplace on corner.

Malecón and

We

decide

that,

at

least once, we should go to

one of the

restaurants at which we had planned to dine.

It was the “Hostal Valencia” and we had “Paella Típica

Cubana”

(wondering what the heck that would be).

It was pretty average, and we returned to the hotel to finish

packing,

and to enjoy one more night, our last fling, in

Sightseeing,

and

shopping,

and

philosophizing,

are all

over – the only thing left is to party on down.

TO BE CONTINUED

We

had

invited

all

our relatives to attend, and

we were

to end up with a party of ten. Besides

the two of us, Diana and Simón, Arturito and Maribel, Mickey and

Silvia (hey! I

just realized, didn’t they do “Love is Strange” in 1958?), and

José Antonio and

his mother Isabelita.

The

price

was

right:

$10.00 (USD) for

foreigners, and

$5.00 (M.N.) [USD $0.25] for Cubans.

Actually, that is probably a pretty fair combination of prices.

At

first

it

seemed

there might be a problem

sitting

together. The first 10 rows are reserved

for foreigners (about the zillionth example of tourist apartheid we’ve

encountered), and when we had gone in earlier in the week to arrange

tickets,

they had said this would be very difficult. But then they worked it out

for us,

and we are all in the eleventh row.

We

stop

for

a

drink beforehand, and I notice

that it is a

good thing I have the guayabera; it seems to be the universal uniform

of the

evening.

When

we

get

there,

I am amazed that the

theatre, which

holds 1500 people, is nearly full. It

has that kind of electric atmosphere that you can sometimes sense

before a

really good event.

At María la O

The

zarzuela

itself

is

spectacular. Lecuona is

a genius, and this operetta is

truly Cuban in the way it combines the Spanish and the African

influences of

the country and its culture, in its plot, and especially its music.

There are a

couple of scenes that are a little too “Stepin Fetchit” for me, but it

was hard

to escape stereotypes in 1930.

Easily

the

most

magical

moments of the week,

and perhaps

of my theatergoing career took place at this performance.

First, in the middle of the first act, as a

comedy scene was finishing and the actors were exiting the stage, the

crowd

broke

into thunderous applause. I thought for

a brief moment “gosh, they weren’t that good.”

Then it became obvious that they were applauding for one or both

of an

elderly couple that had just entered the scene.

The applause grew louder and louder and many shouts of “Bravo!”

were

heard throughout the theatre, when José Antonio leaned over and

told Heide

“That actress is the queen of the

Her

name

is

Rosita

Fornés, a woman in

her mid 70s who has

been on the

In

the

third

act,

when she did her primary

number, “Te

vas juventud,” the applause was even louder, and longer, and after what

seemed

like an eternity of cheering, the crowd slowly got to its feet. The ensuing standing ovation – and wild

cheering -- was probably even longer than the seated applause. It was difficult, if not impossible, to be

there

and still have dry eyes. She certainly

didn’t. Nor did I.

The

applause

at

the

end of the show was equally

effusive,

and it was clear we had attended something really special.

As we left the theatre, Mickey commented,

with appreciative wonder, “I didn’t know ROSITA was going to be here!”

In

the

midst

of

all the poverty and depression

of today’s

La

Mina revisited

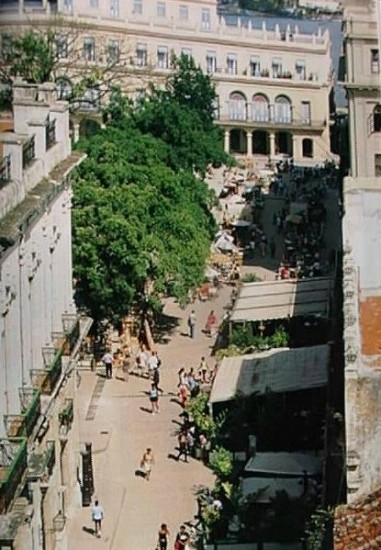

Calle

Obispo. La Mina is the second

awning-covered cafe on the right.

To the

left, under the trees, is the Plaza de Armas, where we ate lunch with a

cardboard spoon on Sunday.

Feeling

like

an

expert

in Old Havana, I herded

all the

relatives to La Mina, where our favorite trio was again scheduled for a

They

played

many

of

the same songs as on

Wednesday, and

as usual, were able to fulfill just about every request.

As we comprised nearly the entire audience,

we had their attention. With my scribbled notes from Wednesday’s

performances,

I was able to pretend I knew something and threw some requests their

way,

An

extra-added

attraction

was

a customer seated

at a

nearby table, who sat in, and sang exceptionally well.

Was he a professional singer, we asked? No,

was

the

answer,

he’s a lawyer from

We

arrive

at

“Dear

Heide:

Thank

you

for your happy birthday

e.mail. I hope you had a very nice day

too. Thanks to your parents I started my

birthday at l2:00

Only

briefly,

a

bit

of sadness crossed my mind

-- it took

this long to bring a great night? Then

suddenly it struck me: “Come on, Emilito: you probably haven’t had such

a great

time in many years either!”

Isabelita

The

final

hours

Virtually

as

soon

as

we were all out of the

plane, we

were all asked to return to the plane, and we took off almost

immediately. It may have been a technical

problem, but

I’ll always wonder if it wasn’t a ruse to get someone off the plane.

The

rest

of

the

trip was pretty uneventful, we

were

picked up at the

Now,

such

a

short

time later (8 May), it seems

hard to

believe we were ever actually there.

P.S. of August 2 1999

Although

But

only

to

visit.

Historical

Addresses

After

I

returned

home

I found out that San

Nicolás 1 was

in fact a valid address. Here, as far as

I can tell, are the addresses of Victorina Gracciani and/or Pepita

&

Antonio in

1906

Inquisidor 14.

Manuel LAGOS TOLEDO lived here. [note of 2010: I can no longer find

where I got this 1906 information]

1907

Inquisidor 14.

Antonio LAGOS TOLEDO lived here.

1908

Consulado 104-106. Paquito LAGOS

GRACIANI born here.

1910

Galiano 125 (now Avenida de Italia). Carmen

1912 San

Nicolás

1. Victorina

1917 San

Lázaro

198. Lolita

1931 San

Lázaro

819. According to oral tradition,

Victorina GRACIANI LORENZO – my

1940 San

Lázaro

661. Maina [Pepita]’s application for a

visa to visit Cuba in 1940 listed this address.

This was where Aunt Betty lived at the time, and where Diana was

born in

1941.

Oh

well,

it's

always

good to have more work to do.

==========

* I since found out Pepita's last name was spelled GRACIANI;

her sister Isabel's, however, was spelled GRACCIANI. Details are found

in http://emilito.org/family/emilito/graziani/finding_graziani.html

)

==========

Cuba trip reports by

emilito:

Family trip to Havana April 1999 - first trip to Cuba since

the Revolution

Rugby trip to Havana September 2000 - Atlantis initiated and

participated in

first-ever rugby sevens in Cuba (PDF only)

Family

trip

to

Havana January 2010 - seven family members travel to Havana for

100th anniversary of their grandfather's marriage

Rugby trip to

Havana

February 2010 - Atlantis rugby trip to Habana

Howlers Sevens 2010

Special reports:

Cubans

on

Cuba

2010 - conversations with some Cubans about the politics of

Cuba

Emilito's

family: early addresses in Cuba - early addresses of

emilito's ancestors and family